|

|

Post by Fading Fast on Oct 12, 2024 9:06:08 GMT

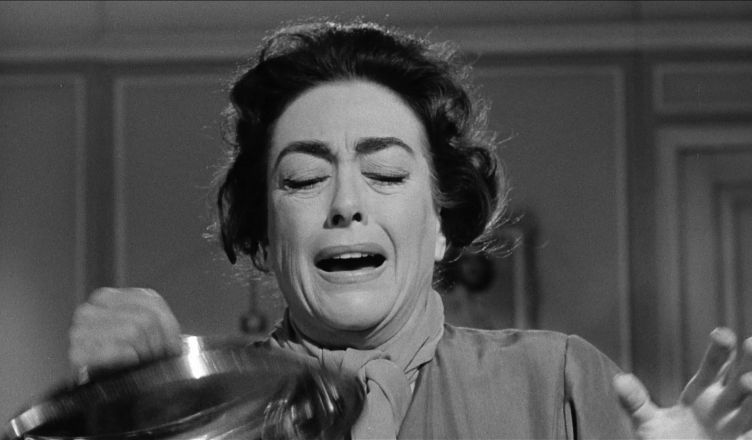

La Notte from 1961 is an Italian film with Jeanne Moreau, Marcello Mastroianni and Monica Vitti

At first you think "intellectuals" see life with a deeper, richer, and more-complex insight, but if the characters in La Notte are "intellectuals," then you might find yourself revising your opinion to see them as intelligent adults who use their sizable IQs to live life like overgrown children.

In this second entry in noted director Michelangelo Antonioni's trilogy (which includes 1960s L'Avventura and 1962's L'Eclisse), bougie, artistic intellectuals find life boring, meaningless, or too materialistic – or something that makes these good-looking, successful people unhappy.

Here, a wealthy heiress, played by Jeanne Moreau, and her successful author husband, played by Marcello Mastroianni, spend a long day and a longer night angstily disliking life, each other at times, and themselves at other times – all because they are bored or disappointed in life.

Shot in beautifully rich black and white, you are in for long scenes of Moreau walking around Milan looking unhappy. These scenes are engaging in a way, but you definitely have to be in the mood for a 1960s "artsy" approach to moviemaking.

You also have to be in the mood for two people constantly talking past each other in a morose way. It's clear their marriage is struggling, but they ironically seem perfectly suited for each other as they can wallow together in their existential angst. Plus, who else would want them?

That question gets answered at the "climactic" (in quotes because there is no real plot here) wealthy person's house party where others like Moreau and Mastroianni drink, eat, dance, get stupid when it rains, and generally try very hard to have fun while "sounding" intellectual.

It's all artsy scenes we've come to know well: an unhappy-looking girl sitting alone, just around the corner from a rambunctious party, or two pretty women, smoking excessively as they talk with feigned nonchalance about the man they won't admit they're fighting over.

Staying with the fiction that there is a plot, Mastroianni meets the daughter, played by Monica Vitti, of the owner of the house who is, get ready for it, bored with her cosseted life. She and Mastroianni flirt, but don't have sex, because it seems, that would take too much effort.

Interrupting the long shots of Moreau being unhappy, are bursts of conversation where the meaning of life, materialism, art and sex are talked about in an off-the-shelf leftist intellectual way. It's like Antonioni wanted to show the French that the Italians can do pretentious angst too.

The movie is beautifully filmed in an stylized way, and Moreau's, Mastroianni's and Vitti's performances are engaging for what they were trying to achieve, but it's hard to sit through two hours of early 1960s intellectual disillusionment unless it is your thing.

It is also difficult to feel sorry for good-looking, successful people who have had many professional or artistic achievements, but still feel life is "so meaningless." This childlike thinking takes our modern phrase, rich-person problems, to even greater pretentious heights.

Today the movie works in two ways. It is still visually appealing and well-acted in the context of what Antonioni was trying to say. It also serves as a time capsule, not so much of Italy at that moment, but of an early example of what would come to be known as 'indie' moviemaking.

If you want to tackle La Notte don't worry about it being part of a "trilogy," as this is no Star Wars: each entry stands on its own angst, depression, and meaninglessness-of-life bona fides. Just don't watch all three on the same day if there are any razor blades in your house. |

|

|

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on Oct 19, 2024 10:01:05 GMT

High and Low a Japanese movie from 1963

It doesn't do it justice to simply call this incredible movie "film noir" as it has impressive elements of a crime drama, a psychological thriller, an ethical dialectic, and social commentary, with each taking center stage at times without any dominating.

More than anything else, High and Low is a series of morality tales and philosophical questions wrapped inside a kidnapping story.

The one big question it raises and leaves for you to answer is if being rich is a moral crime, especially if there are poor around you. It implicitly asks: if you follow the laws of your country, work hard, succeed honestly and become rich, have you in some way stolen from the poor?

Economists' answers to this question usually fall into two broad camps – the same two camps that seem to divide everything. While that question is the movie's philosophical backbeat, a few moral dilemmas and a fantastic police-procedural story drive its plot and tension.

It all opens with a business meeting where we learn a shoe tycoon has leveraged himself to the hilt trying to take over the company he's a minority shareholder in, but then he gets a call that his son has been kidnapped. The ransom demand will bankrupt him, but he's prepared to pay.

It turns out, though, that the kidnapper made a mistake and took the tycoon's chauffeur's son, but the kidnapper still demands the same ransom from the tycoon. This sets up moral dilemma number one: Should the tycoon bankrupt himself for his chauffeur's son?

With the police called in and a smart young detective heading up the investigation, this question gets fleshed out in an amazingly thoughtful way, as the tycoon's life, business and financial security are not simply dismissed as unimportant in an all-out effort to save the boy.

Once that decision is gut-wrenchingly made, the movie becomes an incredibly gripping police drama as the detective heads up an immense team trying to find the kidnapper. The police are impressively modern, skilled, detailed and devoted.

You come away with one thought: It would be very hard to successfully kidnap someone if the Japanese police are committed to finding you, as everything from a tiny sample of scraped paint to an infant's almost comical drawing is smartly leveraged as clues.

The climax doesn't let the tension drop as the search for the kidnapper reveals Japan's seedy world of dope addicts and dealers with an honesty that American films were still a decade away from showing on screen.

Finally, in more of a 1950s crime-drama/capital-punishment-analysis style, the closing scene (no spoilers coming) is a raw examination of the original question about the morality of wealth and poverty living side by side. The question is not answered, but it is powerfully raised.

Based on the 1959 novel King's Ransom by Ed McBain, High and Low is a good story, but what makes this movie great - and it is great - is the acting, the skilled directing by Akira Kurosawa, and the 1960s Japaneseness of it.

Tatsuya Nakadai, a major star, plays the head detective as a thoughtful man who has the skills to inspire others, but also the ability to investigate the clues himself. He is such a competent professional that you'll want him cloned and made the head detective, well, everywhere.

It is an engaging performance that centers the movie as Nakadai's character sits between the tycoon, played by Toshirô Mifune, who plays his businessman like an angry samurai, and Tsutomu Yamazaki, who plays the kidnapper like a ruthless but smart sociopath.

None of this would matter if director Kurosawa hadn't captured, in beautiful black-and-white cinematography, a stark and captivating portrait of 1960s Japan.

He portrays a country that has regained much of the confidence it lost in WWII, but one that is also dealing with all the challenges societies face as rapidly growing wealth is earned by those most driven, talented and lucky.

From Mifune's house on the hill, high above the poverty of the city it overlooks, to the despair of the drug addicts in Japan's version of Needle Park, Kurosawa uses his camera to advance the story and highlight the moral dilemmas raised – though all with distinctly Japanese characteristics.

Japan's unique and deeply held beliefs about honor, respect, saving face, and legal protection for personal property frame a story that challenges all of those values. A boy's life is on the line because a warped anger at the rich creates a scenario where only a rich man can save the boy.

There is so much story, philosophy and raw human emotion at work in High and Low, that it takes several viewings to absorb it all. This is a feature, not a bug, though, in this smartly complex picture that never forgets the first rule of moviemaking: entertain your audience.

To the first question: is High and Low film noir, neo noir, a crime drama, an ethical exploration movie or a psychological thriller – the answer is yes. |

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on Oct 21, 2024 11:26:32 GMT

The Great Man from 1956 with José Ferrer, Dean Jagger, Keenan Wynn, Joanne Gilbert, Ed Wynn and Julie London

Sometimes great movies hide in plain sight, as The Great Man does year after year. It's not obscure and gets good reviews, but it never comes up in discussions of top films or even in discussions about the best movie exposés of the broadcast industry's corrupt cynicism.

Citizen Kane and A Face in the Crowd are regularly noted, but with less fanfare, this José Ferrer co-written, directed, and starred-in effort cedes little to its famous brethren. It is, possibly, even more effective in its relentless reveal of the broadcast industry's arrant hypocrisy.

The picture opens with the death of "The Great Man," a beloved national radio personality we never meet. We learn about him, though, as Ferrer's character, a hard-boiled journalist, is assigned the task of creating and broadcasting the network's one-hour radio eulogy special.

The movie advances on two tracks from here as we see Ferrer investigate the Great Man, while his agent, played with vicious smarminess by Keenan Wynn and the network head, played by Dean Jagger, jockey for control of Ferrer as the Great Man's possible replacement.

It is no real surprise that the "beloved by America" Great Man turns out to be a louse - a selfish, conniving, manipulator of people and abuser of women. It's the old tale of the public image not aligning, at all, with the private person.

Ferrer rolls this story out through his investigation as he learns the dirt about the Great Man in interviews. Watch for the scene where Ed Wynn (yes, Keenan's father) plays the Great Man's first boss and reveals an ugly side of his former employee – it's an acting tour de force moment.

This is a movie full of impressive scenes and performances like that, including one with Julie London playing an alcoholic singer whom the Great Man kept in his stable of women. He helped her career, but also destroyed her self respect. London's performance is gripping.

While Ferrer is learning all the dirt on the Great Man, Keenan Wynn is trying to advance Ferrer's career, but only if he has complete control over Ferrer. Keenan Wynn, though, might have met his match in the network's head, Jagger, who plays the control game at a highly skilled level.

Jagger and K. Wynn’s battles feel like you are a fly on the wall at genuine C-suite meetings, where the gloves come off and ruthless, smart men pull hard on the sinews of authority, money, and control.

Tucked into all this brutal cynicism and jockeying for power is the wonderful relationship between Ferrer and his secretary, played by Joanne Gilbert. It's clear these two have worked together for a long time and developed a deep mutual respect and friendship.

They have an office rhythm that's hard to capture on screen, but they did it here. Yet we so dislike the idea of these relationships today, that we've all but eliminated the word secretary. Yes, there were often many things wrong with those relationships, but not always.

This is one of the not always. It's the warmest and nicest thing in a hard-boiled movie that will wear you down. Look for the scene where Gilbert tries to take a nap in Ferrer's office; it perfectly reflects the nuances of real life that can make a day feel silly and alive.

Gilbert also sees the picture's central conflict playing out slowly and painfully in her boss' inner conflict. Ferrer is going to face a come-to-Jesus moment deciding whether to play ball and give a fluff-piece eulogy or shock the audience with the truth that his reporting has discovered.

Playing ball means career advancement and big money for Ferrer, but it also means dumping his journalistic integrity in the garbage can. There's a neat, as we would say today, meta-twist to the conflict's resolution, just know that people in positions of power get there for a reason.

Though Ferrer wore many hats in the production, he didn't make it a vanity project; instead, he assembled a strong cast and let the story, not his ego, drive the movie.

The result is The Great Man is a great movie about greed, character, corporate power and the ruthless manipulation of public opinion driven by the tightly controlled creation of "personalities," all amplified by the near monopoly the broadcast industry had on reaching the public back then.

The internet and social media have broken that monopoly, so now we have many popular "personalities," tailor made for every subculture. It's more "democratic," but somehow it doesn't feel any better. |

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on Oct 24, 2024 9:17:55 GMT

No Questions Asked from 1951 with Barry Sullivan, Arlene Dahl, Jean Hagen, Howard Petrie and George Murphy

In movies, insurance companies are much more interesting than they are in real life. In noirland, in particular, they often sit somewhere between the cops and bad guys, willing to deal as long as they stay technically within the law.

In No Questions Asked, Barry Sullivan plays a middling lawyer in an insurance company. He has, though, a pretty girlfriend, played by Arlene Dahl, who flat-out tells him she has no interest in being poor or middling. At least give her points for honesty, points she'll later lose.

Sullivan then stumbles into an opportunity to save his company money and get paid a nice bonus for himself by making a deal directly with the crooks who stole some furs. The insurance company gets the furs to return and it pays the crooks a lot less than the price of the coverage.

Sullivan takes his bonus check to Dahl, like a kid with a straight-A report card, but she has just married a rich man. Most men, at this point, would move on, realizing gold-digger Dahl is not the girl you want to marry, but not Sullivan.

Ignoring the advice of the nice girl in the office, played by Jean Hagen, who pines for him, Sullivan sees a business opportunity to become rich and get Dahl back by becoming an independent "broker" between criminals and insurance companies.

As a lawyer, he knows where the legal line is and sets his business up to be just inside of it. His "brokering" company grows quickly, making Sullivan rich and prominent, but not quite beloved.

The police, especially the local inspector, played by George Murphy, don't like his business one bit. It makes the police look bad and, Murphy believes, it encourages crime as the crooks now know they have a "legal" fence in Sullivan.

The last piece of the puzzle is an eccentric mobster, played by Howard Petrie, who sells his stolen goods through Sullivan. He, with his henchmen, then execute a brazen jewelry heist at a theater, knowing they'll have Sullivan to sell the jewels to.

That is the reasonably complicated setup, which we only learn in a flashback, as the movie opens with Sullivan on the run from the police narrating how he got here. Yes, it has a strong echo of another noir set in insurance land, Double Indemnity.

It only gets much more complicated as the picture moves into the third act. The theater jewelry deal goes badly. Then with the police tailing Sullivan closely, Dahl and her husband try to double-cross Sullivan who was still trying to win greedy Dahl back. Some men never learn.

This is film noir under the Motion Picture Production Code, though, so eventually we know all the bad people will pay for their bad acts, but you need a scorecard to keep it straight. Also, Sullivan sits right on the line of probably immoral, but not criminal, so does he have to pay?

Sullivan as an actor is a step below the top men of noir, but he more than adequately carries this B-movie. He lacks that something special that is in a Robert Mitchum or Robert Ryan, but he has a complexity to his mien and cragginess to his face that works well in noir pictures.

Dahl is good as a gold digger cum femme fatale as her avarice seems to grow by the frame. Still, she, like Sullivan, doesn't quite have the look or inner something that makes someone a top-tier noir actor.

Jean Hagan, though, has that special noir ingredient. Having already played the saddest girlfriend ever in noirland in The Asphalt Jungle, she returns for another round of unrequited love. This time, in No Questions Asked, she plays Sullivan's dishrag, while he pines for Dahl.

Look for the scene where Hagen meets her rival, Dahl, face to face. Hagen's a bit drunk and very sad, but she tries to put on a brave face. It's an unusual-for-noir romantically heartbreaking moment in which Hagen completely owns the scene, even when her back is to the camera.

There is a lot of quirkiness packed into this eighty-minute effort, including cross-dressing criminals, a neat test of who is my truly loyal girlfriend and a complete moonshot of a criminal who trains to hold his breath underwater. It's a busy movie.

No Questions Asked flopped on its release. That's surprising as it is a solid low-budget noir near the peak of the genre's popularity.

It checks many noir boxes with its good guy goes bad over a gold-digging woman, oddball crooks, loyal hack driver, cops always one step behind and cheap sets of dark, neon-lit streets, but it didn't sell at the time.

Regardless of why audiences balked back then, today it's a reasonably enjoyable watch. Plus, it's another trip through the fascinating world of insurance companies in noirland, which is one planet removed from insurance companies on earth. |

|

|

|

Post by jamesjazzguitar on Oct 24, 2024 14:36:08 GMT

Watched No Questions Asked twice in the last month or so since TCM had in on Noir Alley and again a few weeks after. The first time I really wasn't that impressed. It was on late Saturday, and I was tried and enjoying my wine. But the second time was in the afternoon and I really was able to focus more on the film (since there is a lot going on in the storyline).

I'm often lukewarm when it comes to Barry Sullivan but here, he shines and is able to pull off the money-is-everything, I don't give a damm attitude.

Jean Hagen gives another fine performance in a noir and is a standout in this film. Dahl looks wonderful and is fine in her role, but I wish another more iconic noir actor played her husband. (but if someone like Steve Cochran had played him, maybe that would have given away the ending?).

That ending and what happens to the pair is really kind of out there, but those two deserved it!

|

|

|

|

Post by dianedebuda on Oct 24, 2024 15:48:06 GMT

Superman Returns (2006) While Lex Luthor (Kevin Spacey) plots against him, the Man of Steel (Brandon Routh) tries to reconnect with Lois Lane (Kate Bosworth) and find his place in a world that learned to survive in his absence. I'm not much into the superhero and comic-book based stuff, but did like the first 2 Supermans with Chris Reeve. Recorded this back in 2015, but put off watching it after seeing how the series had nosedived after the first pair. Was pleasantly surprised that I did enjoy this. Not quite to the level of the earlier pair, but far above the #3. Brandon Routh played his role with many Chris Reeve touches. Kevin Spacey did a good job a Lex Luther, but I kind of missed the intentional, slightly over-to-top Gene Hackman version that gave more of what I'd envisioned as a comic-book villain. Nice to see Eva Marie Saint. Only role that seemed off to me was Kate Bosworth as Lois Lane. Glad they retained John Williams themes and the new score blended nicely. Touched by the dedication to Christopher and Dana Reeve in the credits.

Gee for me, that's a long review.

|

|

|

|

Post by cineclassics on Oct 27, 2024 23:37:29 GMT

I recently watched How Green Was My Valley and it really had a profound impact on me. The film is told in flashback as a young man reflects upon his adolescence and the impact his father had on his life.

I lost my father earlier this year (I'm only 37, so losing a father at a relatively young age has been incredibly difficult). John Ford's Best Picture winner is sentimental, reflective, and despite the many hardships, ultimately a romanticized look at the past. I'm curious, are there any other films that you all would recommend that are similar in tone/theme?

|

|

|

|

Post by topbilled on Oct 28, 2024 0:45:39 GMT

I recently watched How Green Was My Valley and it really had a profound impact on me. The film is told in flashback as a young man reflects upon his adolescence and the impact his father had on his life. I lost my father earlier this year (I'm only 37, so losing a father at a relatively young age has been incredibly difficult). John Ford's Best Picture winner is sentimental, reflective, and despite the many hardships, ultimately a romanticized look at the past. I'm curious, are there any other films that you all would recommend that are similar in tone/theme?

Paramount adapted it as a film in 1963, with Jean Simmons & Robert Preston in the lead roles. This is significant because Preston was one of Agee's favorite actors.

You can watch the film here:

ok.ru/video/6876486240948

For more: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_the_Way_Home_(1963_film) |

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on Oct 31, 2024 8:39:14 GMT

Plucking the Daisy from 1956 with Brigitte Bardot and a cast of others you probably won’t notice – thanks to Brigitte Bardot.

Plucking the Daisy is a silly little French screwball comedy that has three notable features for 1956: Brigitte Bardot scantily clad but not naked, other attractive women briefly naked, and an early 1960s-style mocking of conventional values almost a decade ahead of schedule.

Every sex goddess has her own brand, with Bardot's being a confident youthful spirit that says sex is healthy and fun. Conversely, Marilyn Monroe had a certain girlish innocence to her overt sexuality that, combined with a little teasing naughtiness, created a playful frisson.

Bardot, however, is more straightforward: she knows she’s got it, she’s comfortable with it, and she doesn't think it’s naughty at all. Others might think it's naughty, as in Plucking the Daisy, but that's on them. Her brand of sexuality is guilt-free, but not wanton.

Here, Bardot plays the daughter of a pompous general who worries too much about what others think. When he learns his daughter has written a slightly salacious book under a pseudonym, he tries to send her off to a convent.

Bardot, though, hops on a train to Paris instead and joins her brother in the City of Light, as he's already escaped their father's bullying pomposity. Once there, the screwball chaos kicks up with Bardot first having trouble just finding her brother.

She is helped by a young newspaperman, played by Daniel Gélin – men, for some reason, are always willing to help Bardot. Yet to survive, Bardot sells a rare book from the museum where her brother is an assistant (she thought it was her brother's book).

It's all silliness now as Bardot needs money to replace the book or her brother will get fired, so she enters a striptease competition – you can't make this stuff up. Meanwhile, she's falling in love with Gélin, who works at a newspaper whose city room doubles as a makeout retreat.

There are several twists along the way that eventually sees a masked Bardot advancing in the striptease competition, Gélin falling for the masked Bardot, but not knowing it's her, and the climax coming when the final stripstease competition takes place back in Bardot's hometown.

The cherry on the sundae is Bardot's oh-so-proper father agreeing to be a judge in the striptease competition, which would mean judging his own daughter performing au naturel in front of him – again, you can't make this stuff up.

That's a rough outline of the plot, but Plucking the Daisy, then and now, is not about its plot at all. It's about three things in this order: Bardot, Paris and naked women.

It's a cliché, but the camera simply loves Bardot. Everyone else fades a bit when she's in a scene. Even other very pretty women seem to glow less the closer they get to the sex goddess. Bardot, for her part, is neither coquettish or conceited; blithely confident is as good a description as any.

She's aware she has a God-given sexual allure, but says, "it's not my fault and I'm neither going to aggressively flaunt it nor pretend it's not here: I'm going to live my life as I want and let others obsess over my looks." It's a powerful use of a powerful beauty.

The City of Light, too, shines here as director Marc Allégret captured the post-war metropolis in beautiful black and white. The street scenes and iconic shots, like those of the banks of the Seine, make mid-century Paris look like the most wonderful place in the world to live.

Also easy on the eyes are the naked women in the movie. French cinema in 1956 was clearly different from American cinema as there are a few brief scenes of topless women and naked women shot from behind. It's tame by today's standards, but quite ooh la la for the mid 1950s.

This surprising titillation was at the forefront of the movie’s subversive theme, which mocks old standards of social, cultural, and religious probity, represented here by Bardot’s pretentious father.

That filial rebuke became a standard movie pose worldwide in the 1960s. But the French got a jump on that cinematic sexual and cultural revolution with movies like this one, which for all its screwball silliness, shows a young generation uninterested in the values of its parents.

Today, the fun in Plucking the Daisy is seeing Bardot just before she became an international icon and seeing Paris, because it's always fun to see Paris. The screwball plot quickly grows tiresome, but you can always turn the sound off and just look at Bardot.

While you're doing so, you can't help noticing pretty Paris and the quite early look at the coming "youth revolution," which adduces that all major social change has a longer gestation period than we tend to remember.

Bardot as noted went on to become a sexual and cultural icon, making it fun to see her here on the brink of global stardom. It's a silly movie, but a heck of a Bardot curio.

|

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on Nov 2, 2024 8:46:56 GMT

Fear from 1954, a German Film

It's hard to separate the, at the time, scandalous personal lives and marital woes of director Roberto Rossellini and his wife, star Ingrid Bergman, from this tale of infidelity, but a movie should stand on its own, which Fear does well, though not brilliantly.

Bergman here plays the head of a German pharmaceutical company, where her much older husband is a prominent research scientist. Bergman has been having an affair with a handsome younger man, but she wants to break it off before her husband finds out.

Her husband is suspicious, but if she can make a clean break, all should be well in their otherwise wealthy, almost idyllic life, with their two young children. Affairs, though, are always so much easier to start than to finish. The obstacle for Bergman is the boyfriend's former girlfriend.

The girlfriend, played with a fear-inducing ruthlessness by Renate Mannhardt, is angry that Bergman stole her boyfriend. Mannhardt's revenge is blackmail by threat of exposure, delivered with a Glenn Close from Fatal Attraction combination of crazy and maniacal focus.

That is the setup where, for most of the movie, Bergman is scrabbling hard to get money to Mannhardt to keep her quiet, so that her husband doesn't find out. Look for the scene where Bergman asks her domestic staff to lend her money on the spot to pay off Mannhardt.

Bergman and her husband are about to go away for the weekend when Mannhardt shows up demanding money – the woman's demands are ferocious. This has Bergman frantic to give her money to go away before her husband notices. The tension leaps off the screen.

Bergman's performance is incredible in this scene. She's harried, frightened, and desperate, but tries to remain calm in front of the staff and her husband; a husband who has an inkling something isn't right. Whatever life should be like, this isn't it.

After a few more brutal scenes like that, and with Bergman's husband's suspicion increasing owing to a ring Mannhardt all but ripped off of Bergman's finger, the movie pivots hard in the climax that you want to see fresh, but know a lot changes quickly.

Here too, look for Bergman's performance in the scene when she's finally had enough. She might have been cheating on her husband, but one doubts there's a viewer not rooting for her against the relentlessly vicious Mannhardt by this point.

Rossellini films all this fear – and it is fear – in beautiful black and white and in an upper-class world where everything is so neat and pretty that you can't believe Germany lost a war less than a decade ago.

The juxtaposition of Bergman's gorgeous world of opulent homes, luxury cars, and an office that even looks inviting, against her arrant terror of exposure, sends the same message all affairs-ending-in-blackmail movies (see countless film noirs) send: the affair isn't worth it.

A few different endings were filmed, with the one that made it to the main German version often criticized. But that only matters if the ending matters to you. The real impact in Fear is the fear Bergman lives with throughout; the ending shown is clearly just one possible outcome.

In real life, Bergman and Rossellini's seven-year marriage began and ended in affairs, so the two knew of what they spoke, which probably added to the verisimilitude of this effort.

You can nitpick this or that, the ending especially deserves scrutiny, but Fear got two big things very right: it is visually engaging from the first frame to the last, and no one walks away thinking, "I want to have an affair." |

|

|

|

Post by NoShear on Nov 2, 2024 14:36:04 GMT

I recently watched How Green Was My Valley and it really had a profound impact on me. The film is told in flashback as a young man reflects upon his adolescence and the impact his father had on his life. I lost my father earlier this year (I'm only 37, so losing a father at a relatively young age has been incredibly difficult). John Ford's Best Picture winner is sentimental, reflective, and despite the many hardships, ultimately a romanticized look at the past. I'm curious, are there any other films that you all would recommend that are similar in tone/theme? Condolences on the loss of your father, cineclassics... One film I thought of for you is probably too familiar, but:  |

|

nickandnora34

Full Member

I saw it in the window and couldn't resist it.

I saw it in the window and couldn't resist it.

Posts: 103

|

Post by nickandnora34 on Nov 2, 2024 19:33:52 GMT

I stayed home sick today, and decided to kick off Noirvember 2024 with a few noir films that I haven’t seen before: Just finished The Big Clock (1948) and The Killer that Stalked New York (1950). The former was solid, and an excellent example of the genre, while the latter was merely alright. I do enjoy Evelyn Keyes though.

Anyone else planning to participate in Noirvember? I know the Criterion Channel has a few collections on their streaming service that I plan to get to, and will update as I do.

|

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on Nov 2, 2024 20:18:09 GMT

I stayed home sick today, and decided to kick off Noirvember 2024 with a few noir films that I haven’t seen before: Just finished The Big Clock (1948) and The Killer that Stalked New York (1950). The former was solid, and an excellent example of the genre, while the latter was merely alright. I do enjoy Evelyn Keyes though. Anyone else planning to participate in Noirvember? I know the Criterion Channel has a few collections on their streaming service that I plan to get to, and will update as I do.

I like "The Big Clock" too. The book it is based on is a good quick read as well. |

|

|

|

Post by kims on Nov 4, 2024 16:14:26 GMT

MY COUSIN RACHEL. Wow, can Olivia DeHaviland act. Is she the greedy scheming widow? Is she falsely accused? Is she a loving caring woman? Remember her carefully crafted C

Catherine in THE HEIRESS. Chilling to see her change from innocent into the worst of her father.

She doesn't even make AFI's greatest actresses! Seriously? Who else could have played Melanie in GONE WITH THE WIND? Wouldn't most actresses played her weak, too goody-goody?

She was one of the few actresses who could portray that an innocent can also be strong. And she could be evil like in HUSH, HUSH SWEET CHARLOTTE.

Here's to Olivia!!

|

|

I don't know what else to say about this, except thank you TCM for airing this so I could rewatch in a great print.

I don't know what else to say about this, except thank you TCM for airing this so I could rewatch in a great print.