|

|

Post by Fading Fast on Apr 9, 2024 9:39:57 GMT

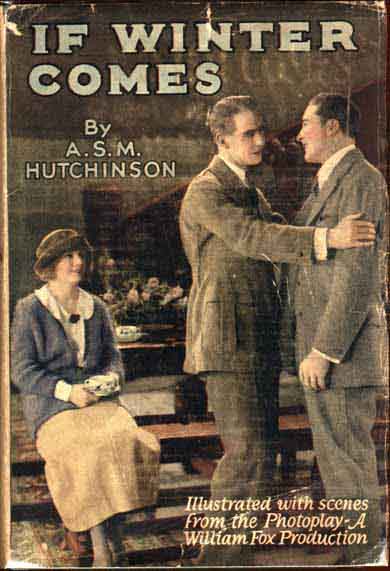

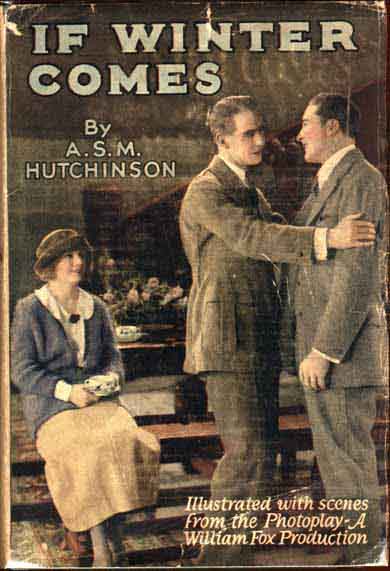

If Winter Comes by A.S.M Hutchinson originally published in 1921

The benefit of old novels today is both their entertainment value - novels are written to be enjoyed - and their window into a past era free of modern biases and agendas. Yes, they have their own era's biases and agendas, but that, too, provides a window into the past.

If Winter Comes is an engaging tale about a man of his time, but one who doesn't quite fit into his time. Mark Sabre is an Englishman when that meant something very specific, but he's too introspective and unwilling to just "go along" to truly fit the mold.

His time, the decades just before and then during World War I, challenged England to look hard at itself and its Empire. We know now that it would take another world war to end that Empire, but WWI was an early domino falling.

Sabre works for a publisher of textbooks, but he's not truly liked at work because he challenges the conventional views too much. After his relationship with his one true love stumbles, he marries a traditional English woman on the rebound.

Most of the book is a look at upper-middle-class England - the merchants and the well-paid salary men - that existed a level below the peerage. They were the vanguard of the “new“ England as the industrial revolution shifted wealth from land to commerce.

Sabre, though, fits neatly into no world. If there is an argument on any big issue - suffragettes, defense spending - or small ones - local zoning rules - he sees both sides of the argument so well that he rarely can decide himself.

It's honorable that he genuinely looks for the truth, but man would still be debating if this new thing called "fire" should be used to cook food or keep us warm if only the Sabres of the world existed.

It's this absolute belief in looking at every angle of an argument and a belief that there is one true justice that eventually gets Sabre into trouble as compromise and even some hypocrisy is the oil that keeps society moving forward.

Most of the book is seeing this good, kind man slowly start to lose his standing at work and at home. His wife is angered by what she sees as his obstinacy to conform to social conventions, especially in England that, at that time, will only bend so far.

Then the war hits and everything eventually snaps for Sabre. The country is stressed as a war it thought it would win in months drags on for years, with a horrific body count of young men.

When the war is nearly all over is when Sabre has to endure a personal war as those who tolerated him at work and at home before the war, now use his integrity against him to try to destroy him.

It's excruciating to see his enemies attempt to crush him as they use the construct of the law and the equally powerful construct of social norms against his forgiving nature. It's the butterfly on the wheel and it's awful to see, but maybe not final.

What is author A. S. M Hutchinson saying? Is Sabre a surrogate for England - an honorable England being undone by arrogance and comfort; an England that traded its values for wealth and security? Hutchinson puts a lot out there for the reader to consider.

Hutchinson is at his best in playing small ball. He sees and understands the intricacies of how people think to themselves as well as the minute gestures and nuances that drive relationships. He has a talent for making his characters come alive.

His writing style, though, is inconsistent. One assumes it's intentional, but he jarringly changes the narrator a few times, while sometimes wandering away from the story's plot to discuss nature or some philosophical issue.

These meanderings are mainly interesting and, for the most part, the story is a good yarn that has you turning the pages, but it does sometimes drive into an odd cul de sac. It's a fast read, but could still have benefitted from some smart pruning.

If Winter Comes was a hugely popular novel that was turned into a play and, then, into a movie twice, once in 1923 and again in 1947. Largely forgotten today, it still provides an insightful look into the past. Plus, it's still a pretty darn good read.

N.B. Comments on MGM's 1947 movie version here: "If Winter Comes" |

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on Apr 24, 2024 10:07:49 GMT

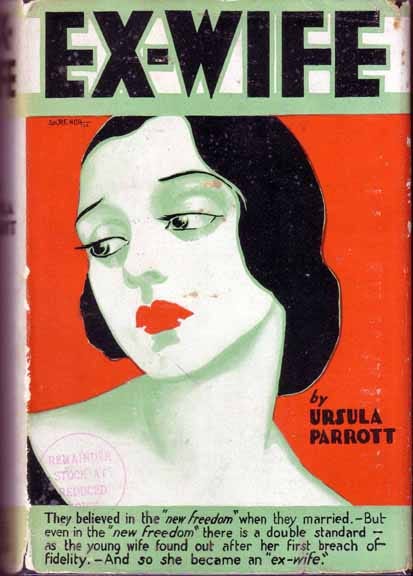

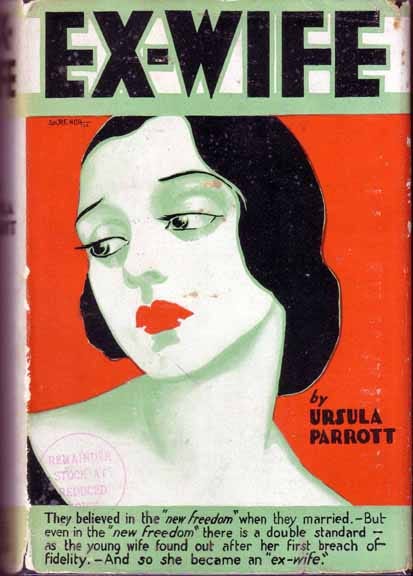

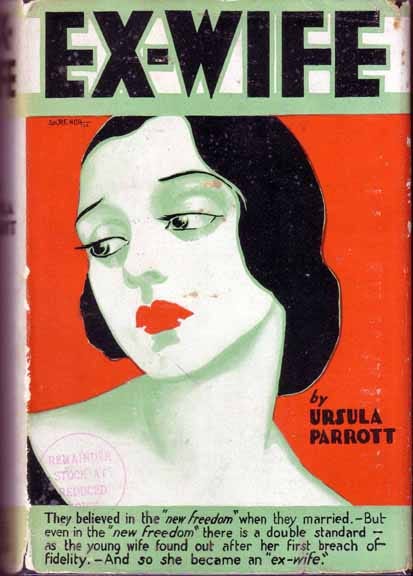

Ex-Wife by Ursula Parrott originally published in 1929

It is striking how late twentieth century Ex-Wife feels. Adjusted for some cultural norms, Ms. Parrott's tale of a young divorcee living in New York City in the 1920s, could have been written in the 1980s or 1990s.

Those latter two decades saw young women, with well-paying jobs, explore sexual freedom in New York City with a joie de vivre that was captured well, albeit with camp, in the TV show Sex and the City. After that, our modern culture wars turned the wheel away from fun.

Apparently, back in Jazz Age/flapper/Prohibition New York City, young women also worked, drank, partied and slept around with little shame according to Ms. Parrott's semi-autobiographical account of "Pat," an early-twenties divorcee.

We first see Pat and Peter's marriage fall apart: he cheated, she revenge cheated and he did not see that as evening the score at all. Pat then carves out a life as a separated and then divorced young woman.

This is where Ex-Wife kicks into modern gear. Pat, now alone, focusess, by day, on her job as a senior advertising copywriter at a department store. She finds she can do quite well, especially with some freelance work on the side.

But at night, Pat and her new female roommate - who live in a quite-nice two-bedroom, two-bath apartment - party like it's the 1980s or, well, the 1920s. They go out to dinner, shows, clubs and "speaks" most nights, often with different men.

Pat isn't sleeping with all of them, but enough that she admits, five years later, she can't really keep track (which was the plot of a Sex and the City episode six decades later). Pat understands that some will see her as "promiscuous," but she knows she's not atypical for her group.

Was she typical for the average American girl in the 1920s? Probably not, as having a high-paying job, being a young divorcee (you can only save yourself once for marriage) and living in a sexually amped up city wasn't the average American girl experience.

Parrott's writing style has a casual moderness to it, note the blunt title. Also, her characters speak with very little of the fussiness one often reads in other books from the era. Again, one wonders how much of that was specific to New York City and not the entire country.

The story gets a bit far-fetched toward the end leaving one to wonder if Parrott took liberties with her own doppelganger story or if there really was a pretty unbelievable twist. It doesn't really matter, though, as the plot is the least important part of Ex-Wife.

What matters is its reveal of a surprisingly modern way of thinking - and talking - in the 1920s. Here, a young woman works hard at a demanding job so she can, yes, pay her rent, but also buy a lot - a whole lot - of clothes and go out partying nearly every night.

Many women out of college in the 1980s and 1990s in New York City did the same thing. After a few years, the successful ones, like Parrott/Pat, started earning good money and spent it on wardrobes and having fun. Again, think Carrie from Sex and the City and all of her shoes.

The women in Parrott's circle also talked frankly about sex. While it's not quite the graphic crudeness of Sex and the City, it's closer to that than the "we don't even use the word 'sex'" reserve seen in movies made under the Motion Picture Production Code.

Even the "my marriage failed, do I need a man to complete myself" theme of Ex-Wife echoes the 1980s/90s. Many young girls, then, had cohabitation relationships that failed. They, like our heroine Pat, were also rethinking their life goals and expectations.

Ex-Wife is incredible time travel to the 1920s. From "girls lunch" at the Waldorf, to the ubiquitous bootleg alcohol, to everyone trying to escape the heat of the summer in pre-air conditioned New York, you experience the city in a Jazz Age way.

Parrott is no Faulkner or Fitzgerald, but she has a writer's eye for detail and, in Ex-Wife, she's following the first rule of writing - write what you know. The result is a page-turner that argues 1920s New York City was surprisingly like its 1980s/90s version.

N.B. #1 One other similarity between women in the 1920s and the 1980s/90s is that Pat works out regularly to maintain her figure. She does calisthenics every morning and uses the running track on the roof of her office building. Who knew they had those in the 1920s? She also hits a commercial gym after work sometimes. It's stunningly modern.

N.B. #2 Ex-Wife was turned into the very good 1930 precode movie The Divorcee starring Norma Shearer. As is Hollywood's wont, though, a lot of the story was changed, but some of the core is still there. Plus Hollywood's version is powerful in its own way. Comments on the movie here: "The Divorcee" |

|

|

|

Post by christine on Apr 24, 2024 17:18:52 GMT

What a vast amount of knowledge and information on this thread. I don't know why I have't visited before other than my excuse is time. I love to read, I love books and I love movies/screen plays taken from books.

Enjoyed the information about IF WINTER COMES. I was fascinated by the 1947 film starring Walter Pidgeon. Always felt it was ahead of it's time.

Great information about EX-WIFE. Made me think about how everything is tied in together. Once again I believe that's why film history is so tied to our history. Whether it's a reflection or an inspiration.

I will definitely be visiting more often.

|

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on May 11, 2024 10:30:14 GMT

A Bear Called Paddington by Michael Bond, original published in 1958

"Please look after this bear. Thank you."

The best children's books can be enjoyed by adults. The best children's books also don't slam you over the head with lessons or, worse, politics, an obnoxious obsession of modern authors of children's books.

If you want, you can read lessons and politics, even modern politics, into A Bear Called Paddington, but that's on you, as the book is best enjoyed for the joie de vivre of a small bear and the loving family who takes him in.

When a little bear, from "the Darkest Peru," arrived at Paddington Station with just the simple note "Please look after this bear. Thank you" written on his lapel, Mrs. Brown knew what she had to do: she and her family had to look after this bear.

Paddington, immediately named for the station at which he was found - and quite proud of his impressive sounding new name - is a handful, a joy and a singular personality. One can only be amazed at the inspiration that led author Michael Bond to create Paddington.

Paddington was sent to England by his Aunt Lucy when she got too old and had to go into "a home for retired bears." Paddington loves marmalade (smart bear) and loves trying new things, but often understands them as only a bear can.

He's kind hearted, but gets incensed at cheaters and mean people. His stare, when he thinks somebody is behaving badly, leaves no doubt as to his displeasure. He's got a rigid, but mainly, well-calibrated sense of justice.

His politeness is indefatigable and a source of much of the book's humor. Even when he's created chaos, eating in public usually leads to unexpected messes, his sincere apologies reveal his genuine surprise that things have gone awry. You just can't get mad at him.

His enthusiasm for life and adventures is contagious, which uplifts the entire kind Brown family. The Browns themselves are part of the wonder of author Bond's world.

All the Browns, Mr. and Mrs. Brown, their two children Judy and Jonathan and their housekeeper Mrs. Bird, take Paddington in stride. Flooded bathrooms, toppled window displays and food everywhere are just part of the experience of living with Paddington.

The Browns all intuit that having Paddington in their lives is such a positive and such an act of kindness - what else could they do, after all, send him out into the world alone? - that all his bear contretemps are taken in stride.

Bond's anthropomorphized bear combines a child-like approach to life - he likes to have his hat and suitcase with him at all times and he is always open to new friendships - with a sensitivity for others that makes him adorable, but neither selfish nor treacly.

There are lessons here about friendship, charity, decency, kindness and family, but they come out of the entertaining and, often, funny tales as opposed to being forced on you.

Bond wrote a total of twenty eight books in the Paddington series and there have been, so far, two enjoyable movies with, surprisingly, the second one being the better of the two. Clearly, Bond created something special in his little bear from "the darkest Peru."

You want to start with A Bear called Paddington as it's always good to get the origin story straight, but it's comforting to know there are so many more adventures to read because, as Paddington says, "Things are always happening to me. I'm that sort of bear." |

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on May 16, 2024 10:26:37 GMT

Until They Sail by James A Michener from the anthology Return to Paradise originally published in 1951

Until They Sail is a long short story from James A. Michener's Return to Paradise, an anthology of essays and related short stories on the South Pacific. The essays are informative but dry, and the short stories are uneven.

Until They Sail and its essay, though, are engaging and evocative, which is probably why the fictional story part of the pair was turned into the very well-done 1957 movie Until They Sail. Hollywood has a talent for knowing what stories will translate to the screen. (Comment on the movie can be found here: "Until They Sail")

In the essay, Michener gives a brief history of New Zealand, including a not politically correct recounting that reveals it wasn't just Westerners who moved in and pushed out indigenous people; here, the early settlers, the Moriori, were pushed out by later settlers, the Maoris.

Michener also explores the tangled history New Zealand has with the United Kingdom, which resulted in the white New Zealanders, like whites in other colonies, often being more "English" and attached to the Crown than many who lived in England at that time.

The real fun in this pairing, though, is the long short story Until They Sail. Four sisters, ranging in age from fifteen to thirty, live in a small but pleasant bungalow with their nearly comatose mother.

Their mother never recovered from the shock of her Naval Captain husband's death at sea early in WWII, so the sisters are, effectively, on their own. Properly raised for their day, their world changes when New Zealand's young men go off to fight in WWII.

For a time, the island is devoid of young men, but this drought turns into a surfeit when American servicemen arrive to defend New Zealand and to use it as a base from which to take back the islands to the north that the Japanese recently conquered.

Until They Sail is a homefront story, though, as it explores what happens when a young female population, wanting for men, runs smack into a wave of young, virile and flush-with-funds Americans, far from home and wondering how much longer they'd be alive.

Each sister responds in her own way. The fifteen-year-old innocently dates a braggart young soldier just to experience dating and kissing, even though she knows he's "a drip." But the second youngest, Delia, goes, well, wild.

Despite being married to a New Zealand boy now being held in a Japanese prisoner of war camp, Delia makes up for lost time by sleeping with a succession of Americans until she finds one that wants to marry her and take her back to America after the war.

The oldest sister, Anne, who is thought "cold" (a euphemism for frigid) and on a path to spinsterhood, surprises everyone by having a love affair with an American officer. He, though, will soon be leaving to fight in the hell that would be Tarawa.

The second oldest, Barbara, the most practical one who takes on the role of mother, tries to manage all these American males swirling around her sisters even as she, herself, begins a gentle flirtation with an American officer.

The story takes several surprising turns including infidelity, an out-of-wedlock pregnancy (when that mattered) and even a murder trial, as Michener packs plenty of drama into this fast-paced tale. One assumes he conflated a lot of real experiences into this one fictional family.

It works because you care about the sisters and because Michener has wonderful raw material to work with -- an atypical moment in homefront history.

Being no more blunt than Michener is, he captured what happened when young, sex-starved women were smashed up against young, sex-starved men, in a time when the normal rules of decorum seemed "suspended."

This is the rare occasion when the movie might just nudge out the book, though, as the 1957 picture is so wonderfully acted and directed that you have a stronger connection with the characters in the film than on the printed page.

The book, however, as almost always, gives you additional background information on the characters and events that help to round out the story. This is one, though, where you might want to see the movie first to experience the picture completely fresh.

Return to Paradise, the full book, is a clunky and somewhat dated effort that awkwardly tries to combine essays and short stories. But being a talented author, Michener did drop one jewel in the center of it with the wonderful homefront tale Until They Sail. |

|

|

|

Post by christine on May 16, 2024 16:24:10 GMT

What fantastic information Fading Fast!

It made me want to investigate Michener further. I found out that one of his first books was adapted into the musical SOUTH PACIFIC by Rodgers and Hammerstein - which I'm a big fan of.

It also seems that most of his fiction writings are about the family unit.

Another book I'm going to search out and add to my reading list! (It's a long list! I thought when I retired I'd have more time for my reading, but it seems that I'm busier now than when I worked. LOL)

|

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on May 16, 2024 16:42:43 GMT

What fantastic information Fading Fast! It made me want to investigate Michener further. I found out that one of his first books was adapted into the musical SOUTH PACIFIC by Rodgers and Hammerstein - which I'm a big fan of. It also seems that most of his fiction writings are about the family unit. Another book I'm going to search out and add to my reading list! (It's a long list! I thought when I retired I'd have more time for my reading, but it seems that I'm busier now than when I worked. LOL) |

|

|

|

Post by christine on May 17, 2024 5:34:20 GMT

Thanks for your recommendation Fading Fast. I'll zero in on "Until They Sail".

|

|

|

|

Post by NoShear on May 19, 2024 15:12:49 GMT

Ex-Wife by Ursula Parrott originally published in 1929

It is striking how late twentieth century Ex-Wife feels. Adjusted for some cultural norms, Ms. Parrott's tale of a young divorcee living in New York City in the 1920s, could have been written in the 1980s or 1990s.

Those latter two decades saw young women, with well-paying jobs, explore sexual freedom in New York City with a joie de vivre that was captured well, albeit with camp, in the TV show Sex and the City. After that, our modern culture wars turned the wheel away from fun.

Apparently, back in Jazz Age/flapper/Prohibition New York City, young women also worked, drank, partied and slept around with little shame according to Ms. Parrott's semi-autobiographical account of "Pat," an early-twenties divorcee.

We first see Pat and Peter's marriage fall apart: he cheated, she revenge cheated and he did not see that as evening the score at all. Pat then carves out a life as a separated and then divorced young woman.

This is where Ex-Wife kicks into modern gear. Pat, now alone, focusess, by day, on her job as a senior advertising copywriter at a department store. She finds she can do quite well, especially with some freelance work on the side.

But at night, Pat and her new female roommate - who live in a quite-nice two-bedroom, two-bath apartment - party like it's the 1980s or, well, the 1920s. They go out to dinner, shows, clubs and "speaks" most nights, often with different men.

Pat isn't sleeping with all of them, but enough that she admits, five years later, she can't really keep track (which was the plot of a Sex and the City episode six decades later). Pat understands that some will see her as "promiscuous," but she knows she's not atypical for her group.

Was she typical for the average American girl in the 1920s? Probably not, as having a high-paying job, being a young divorcee (you can only save yourself once for marriage) and living in a sexually amped up city wasn't the average American girl experience.

Parrott's writing style has a casual moderness to it, note the blunt title. Also, her characters speak with very little of the fussiness one often reads in other books from the era. Again, one wonders how much of that was specific to New York City and not the entire country.

The story gets a bit far-fetched toward the end leaving one to wonder if Parrott took liberties with her own doppelganger story or if there really was a pretty unbelievable twist. It doesn't really matter, though, as the plot is the least important part of Ex-Wife.

What matters is its reveal of a surprisingly modern way of thinking - and talking - in the 1920s. Here, a young woman works hard at a demanding job so she can, yes, pay her rent, but also buy a lot - a whole lot - of clothes and go out partying nearly every night.

Many women out of college in the 1980s and 1990s in New York City did the same thing. After a few years, the successful ones, like Parrott/Pat, started earning good money and spent it on wardrobes and having fun. Again, think Carrie from Sex and the City and all of her shoes.

The women in Parrott's circle also talked frankly about sex. While it's not quite the graphic crudeness of Sex and the City, it's closer to that than the "we don't even use the word 'sex'" reserve seen in movies made under the Motion Picture Production Code.

Even the "my marriage failed, do I need a man to complete myself" theme of Ex-Wife echoes the 1980s/90s. Many young girls, then, had cohabitation relationships that failed. They, like our heroine Pat, were also rethinking their life goals and expectations.

Ex-Wife is incredible time travel to the 1920s. From "girls lunch" at the Waldorf, to the ubiquitous bootleg alcohol, to everyone trying to escape the heat of the summer in pre-air conditioned New York, you experience the city in a Jazz Age way.

Parrott is no Faulkner or Fitzgerald, but she has a writer's eye for detail and, in Ex-Wife, she's following the first rule of writing - write what you know. The result is a page-turner that argues 1920s New York City was surprisingly like its 1980s/90s version.

N.B. #1 One other similarity between women in the 1920s and the 1980s/90s is that Pat works out regularly to maintain her figure. She does calisthenics every morning and uses the running track on the roof of her office building. Who knew they had those in the 1920s? She also hits a commercial gym after work sometimes. It's stunningly modern.

N.B. #2 Ex-Wife was turned into the very good 1930 precode movie The Divorcee starring Norma Shearer. As is Hollywood's wont, though, a lot of the story was changed, but some of the core is still there. Plus Hollywood's version is powerful in its own way. Comments on the movie here: "The Divorcee" Fading Fast, thank you for imparting the exercise enlightenment that marked the flapper's figure...  |

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on May 23, 2024 10:02:10 GMT

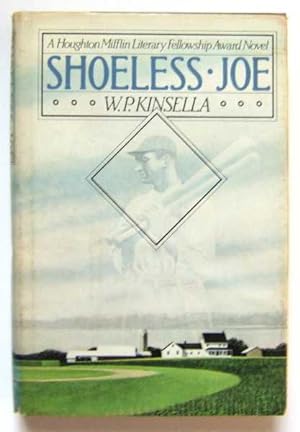

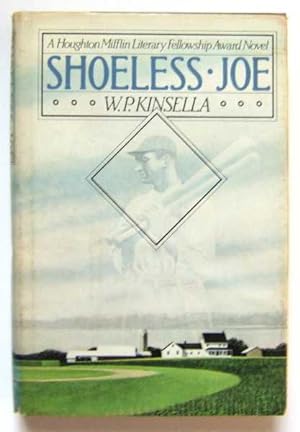

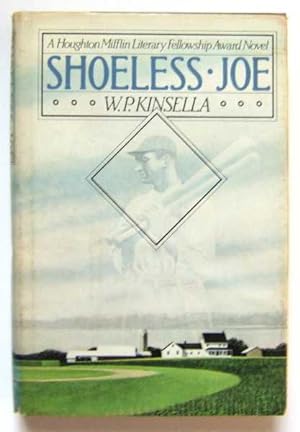

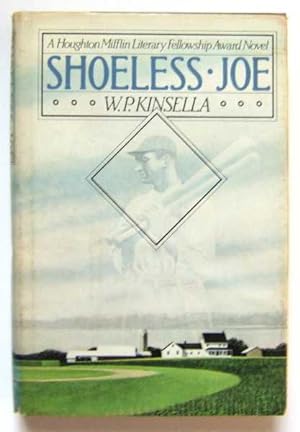

Shoeless Joe by W.P. Kinsella, originally published in 1982

Shoeless Joe by author W.P. Kinsella asks two things of its readers: believe in a metaphysical magic of some sort and be a fan of baseball, not a rabid "my team is the best" fan, but a fan of the history, the lore and the joy of the game.

Those are two fairly specific asks, but if you fit within the lines, the book is a fun and, at times, moving read, even if the writing and story are a bit choppy.

Ray Kinsella, his wife Annie and their five-year-old daughter Karen live on a small struggling corn farm in Iowa. When Ray hears a voice saying, "If you build it, he will come," he eventually determines the voice wants him to build a baseball diamond in his corn field.

The "he" Ray believes is his father's favorite player Shoeless Joe Jackson of the famous "Black Sox Scandal" of the 1919 World Series. Baseball fans will immediately recognize the importance of Shoeless Joe to baseball and, perhaps, American history.

This voice sets Ray, with complete support of his wife, on a journey that sees him not only build a baseball diamond in his cornfield, but also travel a thousand miles to effectively kidnap reclusive writer and baseball fan J.D. Salinger and bring him back to Iowa.

Baseball, here, serves as a framework for several men's lives. Ray's father played professional baseball but never made it to the majors. Instead of telling his young son fairy tales at night, he recounted old baseball stories, including the plight of Shoeless Joe.

Salinger, too, once wanted to be a major league player. In Kinsella's imagination, Salinger is a wounded man who, like Ray and a few others the two pick up along their journey back to Iowa, can find some sort of emotional peace through baseball.

Back at the farm on Ray's field, some form of a game takes place most evenings between players from baseball's past, including of course, Shoeless Joe. Ray, Annie, Salinger and, sometimes, a few others look on.

Some, though, like Annie's greedy brother, who is trying to foreclose on Ray and Annie's farm, can't see the game being played on Ray's diamond. In the brother's eyes, the diamond is just further proof of Ray's incompetence as a farmer, husband and father.

The plot has its share of twists as the fate of the farm hangs in the balance, but the magic of the book is its reverence for baseball, so much so that it envisions a baseball diamond in a cornfield in Iowa as a portal to the past and, maybe, the afterlife.

Morals, values, faith and ideology all get tangled up in baseball's history. Shoeless Joe stands as an example of the gray morality that exists on a continuum between the comic book extremes of pure good and evil few ever achieve.

In Shoeless Joe's plight –– a forever besmirched legacy and a lifetime ban from the game –– we see something of America's loss of innocence. We also see everyone's struggle with morality and, perhaps, we gain a better compassion for human failing.

Tucked inside all this baseball metaphysics and morality is the wonderful marriage of Ray and Annie, who love, respect and support each other. It's nice to see happiness and tenderness thrive in the part of the romance story that happens after the lovers wed.

Shoeless Joe, which was the inspiration for the 1989 movie Field of Dreams, wanders pointlessly here and there and brings in a few unnecessary characters, but it's easy to forgive its faults for all its joy, humor and emotion.

Author W.P. Kinsella wrote a love letter to baseball in Shoeless Joe. At a time when baseball was still, kind of, sort of, the American pastime, Kinsella captured the magic of the game as a metaphor for life and salvation.

That's a pretty impressive achievement for a book that only asks you to have a little faith in the cosmos, a little belief in magic and a little love for baseball's place in the American story.

N.B. Some might remember that I usually read a baseball book or two at the start of spring training each year. Well, I'm late, but I finally got to this year's selection. |

|

|

|

Post by BunnyWhit on May 24, 2024 15:44:45 GMT

Shoeless Joe by W.P. Kinsella, originally published in 1982

Shoeless Joe by author W.P. Kinsella asks two things of its readers: believe in a metaphysical magic of some sort and be a fan of baseball, not a rabid "my team is the best" fan, but a fan of the history, the lore and the joy of the game.

Those are two fairly specific asks, but if you fit within the lines, the book is a fun and, at times, moving read, even if the writing and story are a bit choppy.

Ray Kinsella, his wife Annie and their five-year-old daughter Karen live on a small struggling corn farm in Iowa. When Ray hears a voice saying, "If you build it, he will come," he eventually determines the voice wants him to build a baseball diamond in his corn field.

The "he" Ray believes is his father's favorite player Shoeless Joe Jackson of the famous "Black Sox Scandal" of the 1919 World Series. Baseball fans will immediately recognize the importance of Shoeless Joe to baseball and, perhaps, American history.

This voice sets Ray, with complete support of his wife, on a journey that sees him not only build a baseball diamond in his cornfield, but also travel a thousand miles to effectively kidnap reclusive writer and baseball fan J.D. Salinger and bring him back to Iowa.

Baseball, here, serves as a framework for several men's lives. Ray's father played professional baseball but never made it to the majors. Instead of telling his young son fairy tales at night, he recounted old baseball stories, including the plight of Shoeless Joe.

Salinger, too, once wanted to be a major league player. In Kinsella's imagination, Salinger is a wounded man who, like Ray and a few others the two pick up along their journey back to Iowa, can find some sort of emotional peace through baseball.

Back at the farm on Ray's field, some form of a game takes place most evenings between players from baseball's past, including of course, Shoeless Joe. Ray, Annie, Salinger and, sometimes, a few others look on.

Some, though, like Annie's greedy brother, who is trying to foreclose on Ray and Annie's farm, can't see the game being played on Ray's diamond. In the brother's eyes, the diamond is just further proof of Ray's incompetence as a farmer, husband and father.

The plot has its share of twists as the fate of the farm hangs in the balance, but the magic of the book is its reverence for baseball, so much so that it envisions a baseball diamond in a cornfield in Iowa as a portal to the past and, maybe, the afterlife.

Morals, values, faith and ideology all get tangled up in baseball's history. Shoeless Joe stands as an example of the gray morality that exists on a continuum between the comic book extremes of pure good and evil few ever achieve.

In Shoeless Joe's plight –– a forever besmirched legacy and a lifetime ban from the game –– we see something of America's loss of innocence. We also see everyone's struggle with morality and, perhaps, we gain a better compassion for human failing.

Tucked inside all this baseball metaphysics and morality is the wonderful marriage of Ray and Annie, who love, respect and support each other. It's nice to see happiness and tenderness thrive in the part of the romance story that happens after the lovers wed.

Shoeless Joe, which was the inspiration for the 1989 movie Field of Dreams, wanders pointlessly here and there and brings in a few unnecessary characters, but it's easy to forgive its faults for all its joy, humor and emotion.

Author W.P. Kinsella wrote a love letter to baseball in Shoeless Joe. At a time when baseball was still, kind of, sort of, the American pastime, Kinsella captured the magic of the game as a metaphor for life and salvation.

That's a pretty impressive achievement for a book that only asks you to have a little faith in the cosmos, a little belief in magic and a little love for baseball's place in the American story.

N.B. Some might remember that I usually read a baseball book or two at the start of spring training each year. Well, I'm late, but I finally got to this year's selection. |

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on May 24, 2024 22:13:44 GMT

Shoeless Joe by W.P. Kinsella, originally published in 1982

Shoeless Joe by author W.P. Kinsella asks two things of its readers: believe in a metaphysical magic of some sort and be a fan of baseball, not a rabid "my team is the best" fan, but a fan of the history, the lore and the joy of the game.

Those are two fairly specific asks, but if you fit within the lines, the book is a fun and, at times, moving read, even if the writing and story are a bit choppy.

Ray Kinsella, his wife Annie and their five-year-old daughter Karen live on a small struggling corn farm in Iowa. When Ray hears a voice saying, "If you build it, he will come," he eventually determines the voice wants him to build a baseball diamond in his corn field.

The "he" Ray believes is his father's favorite player Shoeless Joe Jackson of the famous "Black Sox Scandal" of the 1919 World Series. Baseball fans will immediately recognize the importance of Shoeless Joe to baseball and, perhaps, American history.

This voice sets Ray, with complete support of his wife, on a journey that sees him not only build a baseball diamond in his cornfield, but also travel a thousand miles to effectively kidnap reclusive writer and baseball fan J.D. Salinger and bring him back to Iowa.

Baseball, here, serves as a framework for several men's lives. Ray's father played professional baseball but never made it to the majors. Instead of telling his young son fairy tales at night, he recounted old baseball stories, including the plight of Shoeless Joe.

Salinger, too, once wanted to be a major league player. In Kinsella's imagination, Salinger is a wounded man who, like Ray and a few others the two pick up along their journey back to Iowa, can find some sort of emotional peace through baseball.

Back at the farm on Ray's field, some form of a game takes place most evenings between players from baseball's past, including of course, Shoeless Joe. Ray, Annie, Salinger and, sometimes, a few others look on.

Some, though, like Annie's greedy brother, who is trying to foreclose on Ray and Annie's farm, can't see the game being played on Ray's diamond. In the brother's eyes, the diamond is just further proof of Ray's incompetence as a farmer, husband and father.

The plot has its share of twists as the fate of the farm hangs in the balance, but the magic of the book is its reverence for baseball, so much so that it envisions a baseball diamond in a cornfield in Iowa as a portal to the past and, maybe, the afterlife.

Morals, values, faith and ideology all get tangled up in baseball's history. Shoeless Joe stands as an example of the gray morality that exists on a continuum between the comic book extremes of pure good and evil few ever achieve.

In Shoeless Joe's plight –– a forever besmirched legacy and a lifetime ban from the game –– we see something of America's loss of innocence. We also see everyone's struggle with morality and, perhaps, we gain a better compassion for human failing.

Tucked inside all this baseball metaphysics and morality is the wonderful marriage of Ray and Annie, who love, respect and support each other. It's nice to see happiness and tenderness thrive in the part of the romance story that happens after the lovers wed.

Shoeless Joe, which was the inspiration for the 1989 movie Field of Dreams, wanders pointlessly here and there and brings in a few unnecessary characters, but it's easy to forgive its faults for all its joy, humor and emotion.

Author W.P. Kinsella wrote a love letter to baseball in Shoeless Joe. At a time when baseball was still, kind of, sort of, the American pastime, Kinsella captured the magic of the game as a metaphor for life and salvation.

That's a pretty impressive achievement for a book that only asks you to have a little faith in the cosmos, a little belief in magic and a little love for baseball's place in the American story.

N.B. Some might remember that I usually read a baseball book or two at the start of spring training each year. Well, I'm late, but I finally got to this year's selection.

I'm still absorbing its sadness, but I love this split second of pure joy in it:

Mary Hudson waved to me. I waved back. I couldn’t have stopped myself, even if I’d wanted to. Her stickwork aside, she happened to be a girl who knew how to wave to somebody from third base.

Like most boys at that age, I remember the moment when a pretty girl first acknowledged me in a manner that made me know, without yet understanding why, that girls are profoundly different than boys in a very good way.

|

|

|

|

Post by NoShear on May 25, 2024 16:07:41 GMT

Great review, FadingFast. Thanks. It brought to mind J.D. Salinger's story "The Laughing Man" which appeared in the 19 March 1949 issue of The New Yorker. It's a great story, as you'd expect.

I'm still absorbing its sadness, but I love this split second of pure joy in it:

Mary Hudson waved to me. I waved back. I couldn’t have stopped myself, even if I’d wanted to. Her stickwork aside, she happened to be a girl who knew how to wave to somebody from third base.

Like most boys at that age, I remember the moment when a pretty girl first acknowledged me in a manner that made me know, without yet understanding why, that girls are profoundly different than boys in a very good way.

"Shadow Ball":  For me, Fading Fast, the above photo of a now-defunct San Fernando Valley school of my childhood captures both the blurring of baseball's place in American society you wrote of, and a centerfielder eclipsed by the shadows of time... That aged centerfielder, who once read of Tom Sawyer and Becky Thatcher with affection, throwing a nostalgic ode toward your watershed boy/girl experience's direction:  |

|

|

|

Post by Fading Fast on Jul 3, 2024 10:13:37 GMT

The Wheel Spins by Ethel Lina White, originally published in 1936

The Wheel Spins is most famous today for having been turned into the highly regarded 1938 Alfred Hitchcock movie The Lady Vanishes (comments on the movie here: "The Lady Vanishes" ). While the movie deserves all the praise it receives, the book, despite some differences, is an equally engaging, nuanced and suspenseful story.

In White's tale, Iris Carr is a young, pretty, wealthy, orphaned socialite who stays on for a bit when her clique of beautiful friends leaves their remote European resort. A few days later, Iris is about to board a train that, with a few connections, will take her home to England.

Iris, all alone, appears to suffer some sort of heatstroke waiting for the train. She only boards with the help of a frumpy but kindly middle-aged English governess, Winifred Froy, who is returning to England to visit her parents.

As the only two English citizens in their train compartment, Miss Froy chats up Iris despite Iris, still feeling the effects of heatstroke and being a bit of a snob, wishing Miss Froy would leave her alone.

After tea with Miss Froy and now back in their compartment, Iris dozes off. When she wakes, Miss Froy is gone, but Iris assumes she just went to the bathroom or to stretch her legs. Happy for the quiet, Iris only begins to worry after much time goes by and Miss Froy doesn't return.

Iris asks about her, but the others in her compartment either don't speak English or claim to have never seen Miss Froy. Feeling some responsibility for her fellow countryman, Iris makes further inquiries on the train, but everyone denies having ever seen Miss Froy.

Iris can only find two Englishmen who are even willing to help her search. One is a young man attracted to Iris. Adding to the intrigue is the compartment next to Iris' that contains a badly scarred accident victim attended to by a lugubrious doctor and a nun.

The book from here is Iris, still feeling under the weather, pushing, often quite forcefully, for others to help her find Miss Froy, while the whole of the train seems against her. She meets either indifference or repeated outright denials that Miss Froy ever existed.

As the train mechanically rolls on, Iris starts to realize that something sinister is happening, but it's her behavior - claiming a woman no one has seen existed and arguing that the train needs to be searched - that is viewed as suspicious, irrational and even hysterical.

The tension builds as Iris' health flags, others turn more against her - a few threateningly - and even her two early hesitant supporters question her sanity. Author White builds to a powerful climax that has you turning pages with a combination of excitement and trepidation.

White created an atypical heroine in spoiled Iris. She starts off unawarely selfish and haughty as her wealth and lack of parents provide her a comfortable and undisciplined existence. Plus, being English, she absorbed the Empire's superior attitude at that time.

Yet Iris has something better inside her. She wants to dismiss Miss Froy as "just a middle-class governess," but she knows Miss Froy is a human being who needs help and only she can help her. Iris has a good moral northstar underneath her frivolous socialite exterior.

Much of the story engagingly unfolds within Iris' mind, intelligent yet ill-prepared for this novel and dangerous situation. It's enjoyable reading to see this pretty socialite have the mettle to stand up to imperious older women and condescending professional men.

White creates a lot of characters - a supercilious baroness, two cheating spouses, a pair of older arrogant English sisters, a kind English reverend and his wife, a menacing European doctor and others - who make the train a microcosm of class divisions, hypocrisy and envy.

The plot itself is pretty easy, a young woman searches for a middle-aged woman on a train whom everyone claims never existed. Yet, the reason for Miss Froy's disappearance will take you on a tangled trip through international intrigue.

When Alfred Hitchcock turned White's novel into a movie, owing to the needs of that visual medium, he externalized much of Iris' mental angst, made it more of an ensemble story, with an enhanced romantic subplot, and dramatically increased the espionage aspect of the plot.

All those things work very well on screen, which helped to make the movie a classic, but Hitch was working from a wonderful core story with intriguing characters. The joy in the book is reading a story focused almost solely on one unlikely heroine, the iron-willed socialite Iris Carr.

Carr is the character modern writers of period novels should create. Instead though, they make their feminist heroes perfectly align to today's unforgiving and yet tellingly always changing ideal, which makes their book's anachronistic, preachy and often silly and unreadable.

With its taut suspense story, The Wheel Spins sits firmly in the center of the very popular English mystery genre. Yet White's smart insights into human nature, her complex characters and her appealing and unlikely heroine expands the book past the genre's usual boundaries.

The timelessness of her story, writing and characters makes her novel as enjoyable a read today as when it was first published. |

|

|

|

Post by Andrea Doria on Jul 3, 2024 21:53:33 GMT

"Carr is the character modern writers of period novels should create. Instead though, they make their feminist heroes perfectly align to today's unforgiving and yet tellingly always changing ideal, which makes their book's anachronistic, preachy and often silly and unreadable."

So well put and so true for many modern novels. The anachronisms are irritating, but the unforgiving part makes the characters downright unlikeable.

|

|